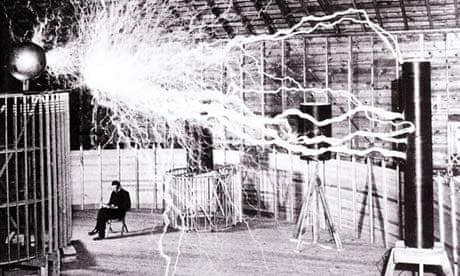

You may have spotted that there is a campaign afoot to buy what was built (though used only briefly) as Nikola Tesla's laboratory and turn it into a museum and science centre. Despite claims of neglect, Tesla evidently commands significant interest, with $500,000 of online donations pouring in within 48 hours.

The campaign is a marriage of the Tesla Science Centre - a group who were interested simply in finding space for the Science Centre located in the Shoreham-Wading River High School to expand - and Indiegogo - the campaign Let's Build a Goddam Tesla Museum run by Matthew Inman of The Oatmeal.

The Indiegogo website opens:

Nikola Tesla was the father of the electric age. Despite having drop-kicked humanity into a second industrial revolution, up until recently he's been an unsung hero in history books.

Calling someone "the father of....", or claiming a "first" usually sets warning bells ringing. This post by historian of science and technology James Sumner explains why. It's also worth pointing out that this "unsung" hero already has an artefact- and manuscript-filled museum devoted to him in Belgrade, a society, and an airport, as well as plenty of interest from historians.

Inman had already produced a comic piece testifying to Tesla being "the greatest geek who ever lived", as "inventor" of alternating current, and a host of other things. Tesla here is the hero not just for his undoubted vision and talents, but for being "a tinkerer" and "a geek". He is contrasted with Thomas Edison, the villain of the piece, who "was not a geek; he was a CEO".

Quite rightly, even though it was comedic hyperbole, Inman's version of Tesla was countered by Alex Knapp at Forbes with the sensibly-named post, Nikola Tesla Wasn't God And Thomas Edison Wasn't The Devil. Overall, the point is that technological innovations require a large number of people and an enormous amount of work to be developed and brought into practical use. Apart from meaning that many more than one individual are responsible, it is also the case that if any of these individuals had not existed, the innovation would most likely have happened anyway.

The Oatmeal - in nice style - produced a response. These pieces are old news, and I don't intend to go through the rights and wrongs of each claim. What strikes me now, in this context, is Inman's characterisations of the two. Tesla is thrilled with pure invention, and typical of "geeks" who "forget food, sleep, friends, love everything", and "abandon the world around them". Edison is a "douchebag", in part for his statement "Anything that won't sell, I don't want to invent. Its sale is proof of utility, and utility is success."

The words sell and success leap out, quickly leading the reader to assume Edison was just in it for the money (as he, like many others, may have been), but let's look at that quote a little more closely. Actually, he says that utility is what he's after - useful things, that people will actually use. Is that so bad? Thinking of the ends as well as the means can be a moral position as well as a business decision.

While I, as someone who deals professionally with scientific heritage, am very much sympathetic to the aim of preserving an early 20th century building designed for scientific work, I harbour a tiny misgiving about what this background to the campaign might do for its future (if all goes to plan) as a science centre.

Science centres, as opposed to history of science museums, tend to present knowledge in a somewhat disembodied way, as packages of information separated from the contexts - the period, the place, the people, the "working worlds" - in which they were produced and used. However, a science centre located in an historic building that brings direct reminders of such real-world things should be a perfect place to explore how science actually happens in the world: looking at science as a process that concerns us all, not just science geeks.

It would be extremely churlish of me not to wish success to a non-profit campaign for an educational facility. Likewise, given the success of the campaign, who am I to argue with the power of fairy-stories? Yet with this connection to a celebration of Tesla as a heroic genius, lauded for choosing to withdraw from the world (despite his large number of patents and involvement with businesses and the military), I fear that the real advantage of the unique location may be lost.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion