Keeping the Tlingit Thought World Alive

The Vaunting Ambition of King Pyrrhus at Butrint

[authors color=”white”]

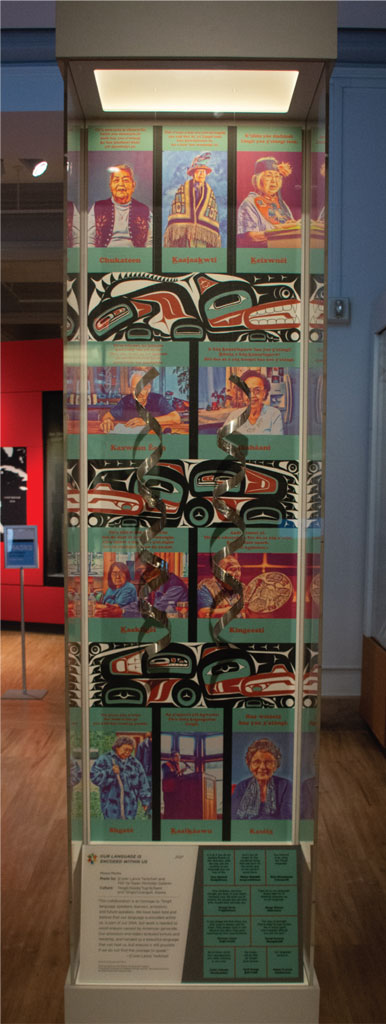

A new rotation of objects in Native American Voices:

The People—Here and Now continues to highlight Indigenous concerns around the themes of local nations, sacred places, celebrations, and new initiatives. A new commission, installed in April 2021, explores language loss and current efforts in the Tlingit language community.

“This collaboration is an homage to Tlingit language speakers, learners, ancestors, and future speakers. We believe that our language is encoded within us, is part of our DNA, but work is needed to avoid erasure caused by American genocide. Our ancestors and elders endured torture and hardship and handed us a beautiful language that can heal us, but erasure is still possible if we do not find the courage to speak.”

— X’̱ unei Lance Twitchell

Our Language Sits Alive Inside of Us

On April 16, 2021, in celebration of the installation of the new commission by X̱’unei Lance Twitchell and Yéil Ya- Tseen Nicholas Galanin in the Native American Voices exhibition, the Penn Museum hosted a virtual event, Our Language Sits Alive Inside of Us, featuring Dr. Twitchell in dialogue with Associate Curator Lucy Fowler Williams.

“The scope of his vision is massive,” said Dr. Williams, introducing Dr. Twitchell. “With methods and practices rooted in kindness and love, he reimagines a future where his grandchildren and allies keep the Tlingit language and thought world alive.” What follows is adapted from their conversation.

Made by: X’̱ unei Lance Twitchell and Yéil Ya-Tseen Nicholas Galanin Culture: Tlingit/Haida/Yup’ik/Sámi and Tlingit/Unangax, Alaska

LFW: Hello and welcome, Lance! How did you develop this installation?

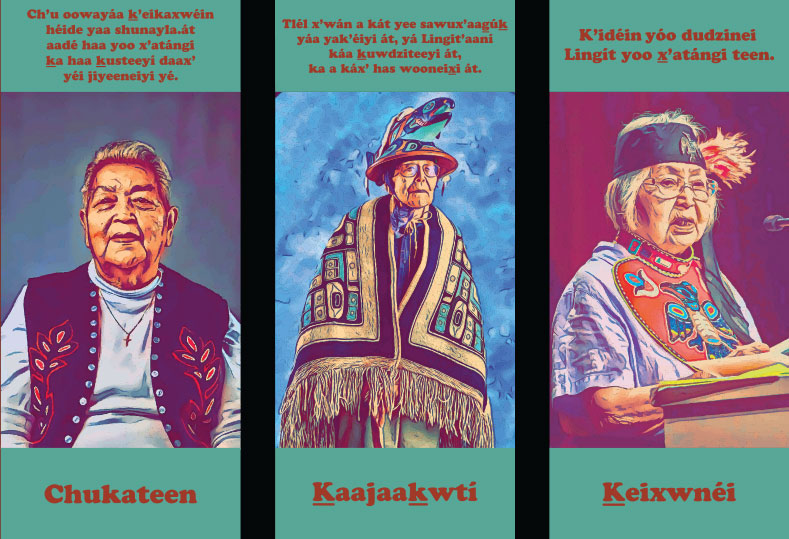

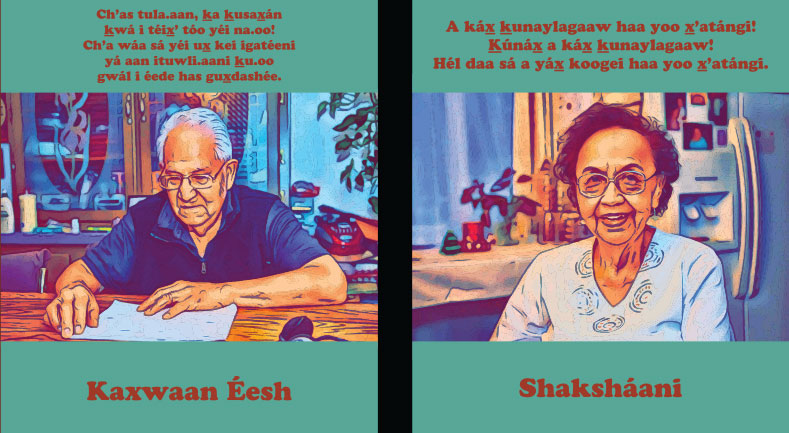

LT: Thank you for reaching out back in 2019. We started out talking about [Tlingit Assistant Curator] Louis Shotridge and his work. Mrs. Shotridge, Florence Dennis, was my mother’s father’s father’s sister, and so she is my great great grandmother. It’s important to make these connections. I thought about the elders I have been so blessed to work with. When I teach Tlingit, I use a lot of their words. I used to go to them and ask, “What do you want your grandchildren to know? Tell me and we’ll teach it to them,” and, “What do learners of Tlingit need to hear to stay motivated and believe in themselves?” From that I received a lot of wonderful ideas, but this is just a little pebble on the beach of a great and vast land. The things they left us give us such incredible strength and reason to go on. There are ten elders on the poster, and when I started the project, probably six of them were alive. Now there is only one, so it’s a bit of a reflection of the state of our language.

I thought about how to visually represent my teachers. Many photographers provided the original images I worked from to create their images. I was thinking of creating a comic-book-like superhero image of each one because they are so incredible.

Of the roughly 25,000 Tlingit people, there are probably 50 speakers remaining. One of these speakers often came to our class and said, “The language, it’s already inside you.” We built from this idea that so much is an awakening.

One fourth to one third of the students who come to study the language are not ethnically Tlingit, but live here in Southeast Alaska. For some who are descendants of colonizers in the United States, to learn an Indigenous language from the place where they live is a beautiful thing because it is a way to say, “I have this complicated history, but I can contribute to an alternative narrative to genocide.”

I envisioned a sculpture that would go in front of the elders. We’ve been engraving silver for a long time, and I had this idea of engraving this repeated pattern of wolf, raven, eagle, and then to spin it so it looks like an abstraction of the DNA strand. This represents the idea that the language is encoded within us.

When you teach a language, there are all the practical elements, such as the sounds that go with each letter. Then you have the abstract concepts and these are pretty difficult to grasp. Then there’s the grammar, which is one of the hardest things ever! And then there’s the psychology of the whole thing. This is about going up against this huge killing machine of American Colonialism, which a lot of people don’t spend enough time examining. In thinking about this silver strand, yes, the language is encoded within us, but the other side is blank. Each of us has to do something; you have to inscribe the other side.

A lot of folks who come to learn the language don’t realize what they are in for. The neurological act of decolonizing your mind through an Indigenous language is a huge undertaking. When students start to grasp the language, it blows them away to meet someone who can speak this way. I wanted to do what I could to honor the things [the elders] gave us, share their comments with the world, and help people see that if you live in North America (and many other places) there is probably an Indigenous language that may be dying right where you live. You can raise awareness within yourself and contribute to the health and life of languages, but it takes work and systemic transformation. All of that is what this piece represents.

When I received the picture of the installation, I was emotional—I miss [the elders] a lot! It was so much fun to hang out with 90-year-olds and talk about how to translate ideas and help people understand the concepts. I am so grateful to the Penn Museum and to the donors that you could make this happen.

You can raise awareness within yourself and contribute to the health and life of languages, but it takes work and systemic transformation.

LFW: Your early design draft included one long strand of twisted silver; The final has two strands. Can you talk about the importance of balance in Tlingit thought?

LT: I am a huge fan of Yéil Ya-Tseen Nicholas Galanin’s artwork, music, and vision. We’ve worked on several projects and we talk regularly about ideas. When I approached him about this piece, I said, “Here is my idea, but you are the master silver carver, so whatever you see, you go.” As he started it became two strands.

There are so many things we call wooch yáx̱ yadál (in balance). We have conversations in both English and Tlingit and, in some ways, the inscribed side is the Tlingit and the other is the English. We all have a clan, which we inherit from our mother. All the clans are divided into two sides, or moieties (Raven and Eagle/Wolf ), and historically, you would marry someone from the opposite side. As a male, your children will always be the opposite clan, and when you speak publicly, that is who you address. This is different than the “living in two worlds” concept, which I think is overly simplified. I like that the two silver strands move and spin.

LFW: Help us understand the complexity of your language and its deeply guttural pronunciation.

LT: We have 61 known sounds in Tlingit. Twenty-four of them are not in English, and of course English has sounds Tlingit does not have—R and F, for example. Imagine creating a teaching curriculum to play the violin when there is no F sound! We do have the one symbol for one sound relationship and you can learn to read and write fairly quickly. We have four vowels and their variations. Then we get into the thought world ideas, such as how distance and time work in the language. And the verbs are fascinating. We have, for example, 20 words for swim depending on how you are swimming, and 15 words for carrying something because it depends on what you are carrying.

It is as if you all are leading flowers in this direction, with the way you are working on our language and our way of life.

Kaajaakwtí | WALTER SOBOLEFF

Don’t you all forget it! This wonderful thing that was born on the world, and on the world it saved them.

Keíxwnéi | NORA DAUENHAUER

You improve it by using the Tlingit language.

Be of brave spirit! Your grandparents are really listening to you now.

Kaalkáawu | CYRIL GEORGE

My prayer will be this: let Tlingit exist forever.

Kaséix | SELINA EVERSOM

Our language saved us.

Only kindness and love, though, put them in your heart! However your life goes out of control, the people you are kind with, maybe they will help you.

Shaksháani | MARGE DUTSON

Fight for it, our language! Really fight for it! Nothing measures up to our language.

It was always the first thing, too, they used to always care for them. They always used to talk about it: the place they were reserving for their grandchildren.

Kingeestí | DAVID KATZEEK

The way of strength. That is what he says to him: “Be of brave spirit! Life is always difficult. You will not quit.”

LFW: How do you keep students motivated to learn?

LT: One of my emphasis areas is creating a safe learning environment. We are doing experiments to consider what would happen, for example, if we broadcast all our classes on the radio. We are trying to find an alternative to the tuition model that higher education depends upon. There are certainly discussions to be had about state funded educational institutions charging tuition to Indigenous students to learn their own languages that were taken by the American education system. We’ve done lots of fundraising and there are scholarships. Students don’t have to pay anything, and we never turn anyone away as long as they are helping us maintain a safe learning environment. By safe I mean that we must be careful correcting students and giving feedback, and it is always okay to make errors. America trends towards a monolingual existence, which is hugely problematic for all kinds of people who come from other places, speak other languages, or want to hold on to their accents. For Indigenous peoples, if we lose our languages, they are quite likely gone forever.

LFW: What is a language nest?

The Hawai’i P-20 concept is a language medium education system from preschool through Ph.D, with “language medium” meaning that all content is taught through Hawaiian. This is one of our goals. It is daunting because if you have a language with fewer than 100 speakers, and as few as 10 in some communities, what does this future look like and how do we construct it?

…if you don’t speak it now,

you will have to speak a different life.

LFW: Visitors to our gallery can access your video through a QR code on their cell phones and hear you speak in Tlingit and English.

LT: I am happy to have their voices in your museum. The history of Indigenous peoples in museums is infinitely complex. So many of our things are there, and more in a single museum that features Tlingit collections than in an entire community or clan. Some say there are more Indigenous human remains in colleges and universities than our people on the earth. The level of disconnect, trauma, and horror that this brings is something we don’t talk about enough. Indiana Jones is a hero for some, but he is not going in to raid the tomb of King Henry and take the crown from his head. He’s digging up Indigenous peoples, and the glorification of this is problematic. While some things are legitimately acquired, sometimes things are just taken. In our language work we keep things private so that no one will take the things that belong to our medicine people.

The counterargument is that we can bring our voices into museum spaces so you can hear and learn from us. There have been repatriation ceremonies and actions that are steps in the right direction. We didn’t make things to hang on walls or sit in cabinets. These are living things that are supposed to be used. Nora Dauenhauer said, as we lined up all of our belongings, that it was like seeing the faces of her ancestors who are gone. For us, this is part of a huge disruption, and to close these fissures we work on our own language and with partners to say, let’s put some more of our work in there and let’s make some room because we need to get more of our things back home. We need more partnerships and more ideas on how to do that and to construct our own facilities so we can care for those things. We do have hats that are hundreds of years old; We still have them and still use them.

We are an impoverished people who have lost so much, but I think there are ways to work out destinies that are different than what we are being convinced is going to happen, which is language loss and death, and people and things frozen in museums.

LFW: What else should we know about your work?

LT: In Alaska, we are trying to transform education to a place where languages live and are a main part of the curriculum. We are also working on how to create pockets of learners and get them to commit. We don’t want to put too much pressure on our students, but we also must tell them that if you don’t speak it now, you will have to speak a different life. We have tripled our class enrollments.

I am imagining a future where we get the state of Alaska to commit to teaching as many languages as we can, without charging tuition. There are religious, state, and federal entities with a lot of mud on their hands. A public apology goes a long way. This is not an anti-religious statement, but they actively prohibited Indigenous language speech. One individual in this art piece—hearing her tell her life story in Tlingit just breaks my heart. They beat her, scared her, yelled at her, humiliated her, laughed at her—everything they could. But she did not stop speaking her language. She was such a wonderful speaker: kind, courageous, and hard core! She really informed the work I did.

There are more conversations to be had about social accountability and how we can collectively be more conscious of Indigenous languages and take responsibility.

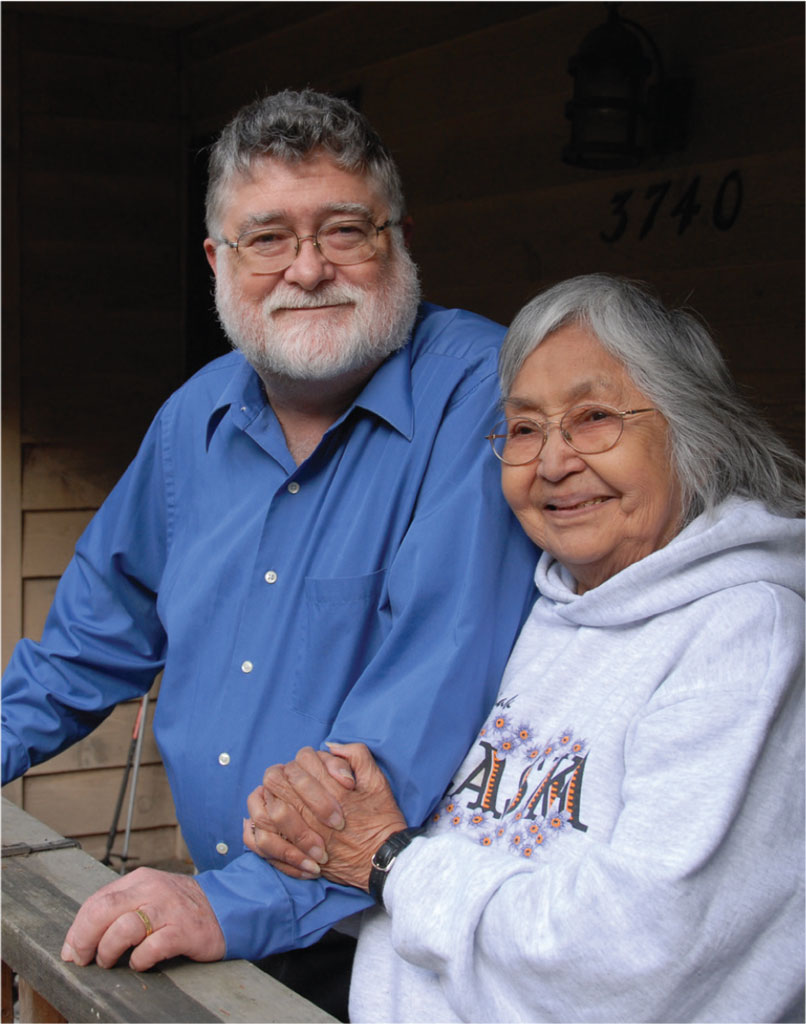

X̱’unei Lance Twitchell, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Alaska Native Languages at the University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau. He teaches the Tlingit language and courses on writing, poetry, Northwest Coast form-line design, and oratory. His dissertation tackles the erasure of the Tlingit language through U.S. government assimilation. Acknowledging the magnitude of loss and suffering, he charts a solution and creates a curriculum to strengthen and revitalize Tlingit speakers. Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D., is Associate Curator and Sabloff Senior Keeper of Collections in the American Section of the Penn Museum. A cultural anthropologist, her research interests include issues surrounding Indigenous identity.

The Penn Museum and the authors would like to thank Gerri and Dolf Paier and George and Elizabeth Gephardt for making this commission possible.