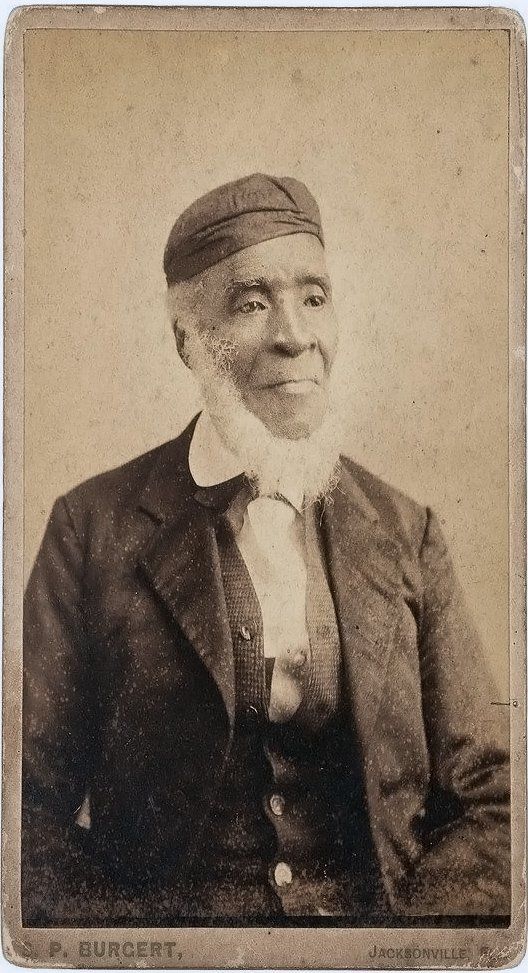

The Life of Luis Fatio Pacheco: Former Slave and Scout for Major Dade

As we usher in Black History Month, we begin by spotlighting the remarkable story of Luis Fatio Pacheco, a figure deeply intertwined with a pivotal moment in American history. Born into slavery, Pacheco’s life was marked by events that shaped not just his own destiny but also left an indelible imprint on the landscape of the Second Seminole War. His role, particularly in the Dade Massacre, highlights the complex interplay of loyalty, survival, and agency in the lives of enslaved individuals during tumultuous times. Pacheco’s story offers a unique lens through which to explore the intricate and often overlooked narratives of African Americans in the fabric of our nation’s history, making him an essential figure to remember and learn about as we delve into the richness of Black History Month.

Who Was Luis Fatio Pacheco?

Luis Fatio Pacheco’s journey began in 1800, born to enslaved parents on the “New Switzerland” plantation in Florida. His upbringing on Francis Phillip Fatio’s estate, nestled along the St. John’s River, was anything but ordinary. Surrounded by a diverse mix of Africans, Seminoles, Spanish, British, and Americans, Luis’s early years were steeped in a rich cultural milieu. This exposure not only shaped his understanding of various cultures but also saw him become fluent in several languages including French, Spanish, English, and Seminole. His multilingual skills would later prove invaluable.

Despite the privileges afforded by his father’s skilled status, Luis’s life was upended following the Seminole destruction of the plantation in 1812, a retaliation against local planters supporting American annexation. The upheaval led to numerous relocations for Luis and his family, ultimately bringing them to the San Pablo plantation. Here, Luis was entrusted with the significant responsibility of a mail courier, a role that highlighted his reliability but was short-lived as Florida transitioned to U.S. control in 1821. His personal life was equally tumultuous, marked by his marriage to a freedwoman and his frequent, unauthorized visits to see her, underscoring his longing for freedom.

Luis’s pursuit of liberty reached a pivotal moment in 1824, following a severe conflict with Lewis Fatio, his young master, driving him to flee to the Spanish fisheries on Florida’s Gulf Coast. Despite his strategic refuge, leveraging his linguistic abilities and connections, he was captured by the American military in 1825 and taken to Fort Brooke. There, his unique skills in languages, carpentry, and literacy were recognized and valued by successive military commanders. In 1832, his life took another twist when he was sold to Antonio Pacheco, a Cuban trader. Upon Pacheco’s death, Luis became the property of Pacheco’s widow, marking yet another chapter in his eventful life.

Heading to Fort King

In December 1835, with tensions escalating between the U.S. military and the Seminoles, Major Francis L. Dade was set to lead a troop detachment from Fort Brooke to Fort King. Captain Francis S. Belton, the officer in command at Fort Brooke, recognized the need for an interpreter in this delicate mission. Belton chose to enlist the services of Luis Fatio Pacheco, known for his linguistic skills and familiarity with the Seminole language. To facilitate this, Captain John C. Casey, serving as the acting assistant quartermaster at the fort, was tasked with arranging the rental of Luis’s services. He negotiated with William Bunce, the executor of the Pacheco estate, settling on a monthly fee of $25 for Luis’s expertise. This arrangement underscored the strategic importance of Luis’s skills in the impending conflict with the Seminoles.

Surviving the Massacre

Luis Fatio Pacheco’s survival during the notorious Dade Massacre in December 1835 is a tale of linguistic prowess and quick thinking in the face of imminent danger. Major Francis L. Dade, leading a troop detachment to reinforce Fort King, was more focused on the need for soldiers than interpreters, expecting combat with the Seminoles rather than negotiations. Despite this, Dade assigned Pacheco the role of a scout. In his reconnaissance missions, Luis detected early signs of Seminole hostility and attempted to warn Dade. However, Dade, a Virginia slave owner, disregarded the advice from a slave.

This oversight proved costly. On December 28, as the troops neared Wahoo Swamp (Bushnell), they were ambushed by the Seminoles, unprepared with their coats covering their cartridge boxes. Dade was among the first to fall. The situation seemed dire for Luis, but his unique skill set – particularly his fluency in the Seminole language – became his lifeline. He pleaded for his life, arguing his status as a slave following orders. This appeal to the Seminoles spared him from immediate death.

Following the battle, Luis was captured and lived with the Seminoles for nearly two years. His first attempt to escape by canoe failed, leading to his recapture. However, Luis persevered and managed a successful escape. On September 4, 1837, he turned himself in at Fort Peyton near St. Augustine, surrendering to the military authorities. Luis identified himself and declared his belonging to Mrs. Quintina Pacheco. His ordeal and eventual surrender highlighted the complex dynamics of the time, particularly for those like Luis, who navigated a world of shifting allegiances and identities.

Accusations of Betrayal

The case of Luis Fatio Pacheco, brought before the U.S. Congress in 1842, sparked significant controversy, painting him as a key figure in the Dade Massacre and a subject of political manipulation. John Lee Williams, a St. Augustine resident, first accused Fatio in 1837 of collaborating with the Seminoles. Williams claimed that Luis frequently left the troop formation during the march and quickly joined the enemy after the first gunshot. The basis for Williams’ accusation remains unclear, though it’s speculated that Fatio’s connections with Black Seminoles may have played a role, either through familial communication or direct identification among the Seminoles.

Fatio’s survival was confirmed in 1841 when he appeared during negotiations between Seminole leader Coacoochee and U.S. General Thomas S. Jesup. Coacoochee claimed Luis as his property, captured in war, and Jesup consented to Coacoochee taking Fatio, along with several Black Seminoles, to what is now Oklahoma. This event led to a claim by Antonio Pacheco’s heirs for compensation from the U.S. government, arguing that Jesup’s decision deprived them of their property. The Joint Committee on Claims, dominated by slaveholders, approved this payment.

This case became a focal point in Congress for debates on slavery. Abolitionists used Fatio’s story to criticize the government’s financial support of slavery. In 1858, Representative Joshua R. Giddings of Ohio published a book portraying Fatio as a defiant rebel against U.S. slavery. Giddings presented Luis as a revolutionary, suggesting his involvement in the Dade Massacre was an act of rebellion and a statement for freedom, thereby making him a symbol in the fight against slavery.

However, Fatio’s own account, shared in an interview with the Daily Globe-Democrat, offered a different perspective, one that was lost amidst the political use of his story. Without his personal narrative, Luis Fatio Pacheco would have remained a mere symbol in the larger debate, utilized by different sides for their respective causes. His story thus illustrates how individual experiences can be co-opted and reinterpreted within larger socio-political contexts.

Did He Help the Seminole?

The question of whether Luis Pacheco betrayed Major Dade during the infamous Dade Massacre has long been a subject of debate, with compelling arguments on both sides.

The Case for Betrayal

On one hand, contemporaries of Pacheco, including high-ranking military officials like General Thomas S. Jesup, were convinced of his betrayal. Jesup, a key commander during the Florida war, alleged that Pacheco was in continuous communication with the Seminoles from the moment Dade’s command left Tampa Bay until its defeat. Although Jesup did not specify the evidence he had, his assertion was strong enough to influence others’ opinions. Historical figures such as Mrs. Minnie Moore-Willson, who wrote extensively about the Seminoles later in the 19th century, also shared this belief, adding credence to the notion that Pacheco had indeed betrayed Dade by informing the Seminoles of the detachment’s movements, thus facilitating their ambush.

Fatio’s Defense

Conversely, Luis Pacheco himself provided a different perspective in an interview with the Daily Globe-Democrat. Fatio portrayed himself as a victim of circumstances, caught between nations at war and their conflicting interests in enslaved individuals. He claimed to have attempted to warn Major Dade about a potential Seminole attack, only to be dismissed and laughed at. After his capture by the Seminoles, Pacheco argued that he was considered “enough American” by them to be kept as a prisoner of war, rather than being allowed to return to his people. His narrative suggests that both the Pacheco family and the Seminoles viewed him as an asset, either for his monetary value or as a war trophy. Upon his return to Florida, Fatio actively sought to share his side of the story, possibly to mitigate any hostility or threats against him, and to peacefully reintegrate into the society he had left.

This dichotomy presents a complex picture of Luis Fatio Pacheco’s role in the Dade Massacre. While some viewed him as a betrayer, his own accounts, and the situations he found himself in paint a picture of a man navigating a perilous landscape of war, slavery, and shifting allegiances, striving to protect his own life and interests amidst tumultuous times.